The final installment of Peter Jackson’s Hobbit trilogy—controversial among even Tolkien fans by being a film trilogy at all—is nearly upon us! But although The Battle of the Five Armies is about to begin, the Extended Edition of The Desolation of Smaug has only just arrived.

The theatrical cuts of Jackson’s films are as CliffsNotes to me, where the Extended Editions are the unabridged forms. Marketers tout these editions as “extended,” but you’ll notice these are not called “deleted scenes.” And for good reason. In most cases the Rings and Hobbit “extended” scenes are actually integral to the plot but don’t necessarily provide vital information to the broader movie-going populace. And I get that; many complain that the movies are long enough already, or that they should have been crammed into fewer films. For those of us more invested in Middle-earth—in Jackson’s Middle-earth, to be clear—they’re like comfort food. Tastier and more satisfying.

As written previously, I’m a hardcore Tolkien fan and a Peter Jackson apologist, so my review of this film is optimistic even though I agree with the masses that some of Jackson’s meddling is overwrought or far too pandering to the action movie crowd. But if you’ve even an inkling to know what was left out of the theatrical Desolation, read on!

The phrase “the Desolation of Smaug,” which subtitles the film, does not exist within the text of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit—only on Thrór’s map of the Lonely Mountain as it appears in the book. Within the narrative, Tolkien refers to the wasteland around Erebor and Dale only as “the desolation of the Dragon.” I find that this shifted emphasis on Jackson’s part is a fitting analogy to his selective emphases in the films themselves—a fact which many Tolkien fans decry.

But after six films and the director’s long-established reputation for not making his films match the books exactly, as so few film adaptations do their literary counterparts, I say it’s also time for moviegoers to accept that Peter Jackson’s is merely a new version of Middle-earth, not a replacement. (No different than J.J. Abrams’s alternative Star Trek timeline or the cinematic Marvel universe.) It doesn’t ruin anyone’s childhood. Read the books to your kids first, if you prefer it. I certainly shall!

First of all, it’s worth noting that TheOneRing.net is an excellent place to find comprehensive coverage and discussion of everything even peripherally related to all six Middle-earth films, including a blow-by-blow analysis of film trailers and extended editions. Here I’ll just address the extended scenes of Desolation more contextually.

As I see it, the extended scenes, interwoven in the film more sporadically than previous installments, each fall into one of two categories: (1) material that brings a little more of the book back into the movie and (2) material that speaks to the larger narrative of The Lord of the Rings trilogy itself. One could argue that the former scenes are actually more important, since universal criticisms target Jackson’s many and bold deviations from the books. And frankly, the book is oozing with charm and I’m glad to see some more of it show up here.

Based on the chapter “Queer Lodgings,” the first of the book-based extended scenes shows how Gandalf introduces Bilbo and the dwarves to the ornery Beorn the next morning when the skin-changer is chopping wood. In the books, they don’t get chased into his home by Bear-form Beorn but rather simply show up two by two so as not to overwhelm/anger their host. While of course still shortened, the scene does an admiral job of paying respects to the humor and wit of the book. Moreover, in a film where Bilbo is too quickly upstaged by action and heroics, it feels good to see the titular hobbit being meek and a wizard being nervous.

I also love reminders of how Gandalf fits into the world: not everyone’s heard of him or has even a vague notion of his real power. Here he is humble and respectful, aware that diplomacy is needed to secure help in reaching Mirkwood with orcs on their trail. Of course, the orcs are not as much of a threat in the book since Bolg doesn’t come into the picture until the Battle of the Five Armies. Just the same, Beorn will return in that battle and it’s good to see more of him now.

On the edge of Mirkwood when Gandalf is leaving Thorin’s company, he warns them this time of a stream in the forest that carries a “dark enchantment” and not to touch the water. Which is the next book-based scene, based on the “Flies and Spiders” chapter. Instead of a boat on the far side of the stream, roots and vines present the only way across. Bilbo traverses it first, and it’s clear the enchantment is one of sleepiness, and nearly succumbs to it.

When they (mostly) reach the other side, a fairly-glowing white hart appears on the dark path ahead. Bilbo and Thorn stare in wonder, but while the hobbit feebly protests, Thorin takes a shot at it and misses. Which is interesting, because he does so in the book because they are out of food and in need of the venison while here it feels more like an impulse of frustration at the “accursed forest.” Bilbo remarks that it’s bad luck to have tried, then Bombur falls into the stream. (In the book, the hart itself, which Thorin succeeds in hitting, actually knocks Bombur into the water.)

The result is a heavy, sleeping dwarf the others are forced to carry as they toil on through the forest. Although one of the films’ best qualities are the fleshed- out and distinct personalities given to all the dwarves (where Tolkien was minimal on this), it is sadly not addressed here whether Bombur’s immersion in the enchanted water has any effect on his memory. Considering how little Bombur speaks in the films, I suppose it doesn’t matter too much. It would have been a nice touch to see the extended scenes fill in the story further still.

Really, anyone who spends money on the Extended Editions is already not in the cut-the-films-down-to-fewer-movies camp, anyway. This one has 25 minutes of extra film time; a lot of us would happily add an hour or so to the running time. I recall reading about Bombur’s memory loss as a kid and thinking how horrible it would to be to have forgotten half of the adventure so far: the trolls, Rivendell, the Misty Mountains, Beorn! Gah, those were awesome!

The journey through Mirkwood is also rightly extended—alas, only by a few minutes of screen time. In the theatrical version, the forest seemed far too small and hastily passed through and with no risk of starvation. This time, instead of simply losing the Elf-path Gandalf told them to stay on, Thorin, muddled by the stifling illusions of the forest, seems to deliberately lead them off it.

Of the spiders, Elves, and barrel journey to Lake-town, nothing new was added. But the company’s journey up to the Lonely Mountain is given a slight extension as Bilbo remarks how quiet the countryside is. As Balin mentions the birdsong there used to be there in the time before the dragon, Bilbo looks with interest (or remembrance?) at a thrush which lights on a rock. A simple, thoughtful reference to the prophecy about to unfold. How I wish this bird would later deliver to Bard the news of Smaug’s missing scale! But the films don’t seem to adopt the talking-beast precedence of the book. If they had, the Eagles would have been talking by now.

As for the “bigger picture” extensions, there are essentially three: Beorn, Bard, and Thrain. Beorn’s first extended scene has already been addressed, but there is another. When he is setting up Thorin’s company with borrowed ponies, he and Gandalf exchange some exposition. It’s an informative set-up, although hearing the hermitic Beorn know so much about their enemies sounds forced. He has the eyes and ears of countless animal friends, to be sure, but his knowledge of Moria, Dol Guldur, homages, and alliances is clearly strained for our benefit. And of the Necromancer, Beorn says, “I know he is not what he seems,” echoing Galadriel perfectly. Too perfectly.

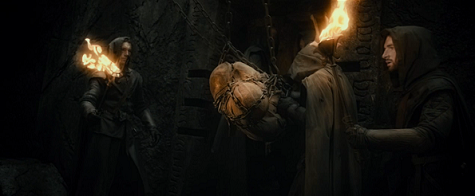

He warns Gandalf that “the dead have been seen walking near the high fells of Rhudaur.” Why would he know this? Because this lets Gandalf recall the words of the Lady of Lórien (and gives Cate Blanchett a cameo) when she spoke of what became of the body of Angmar (i.e, the lord of the Nazgûl, who is often referred to in Tolkien lore by the realm he once ruled). In turn, we’re treated to a visual of the wrapped and chained body of the soon-t0-be Witch-King.

In Jackson’s films, discovery of Sauron is first clued in by the release of the ringwraiths from their tombs. So it is Beorn’s words here that push Gandalf one step further along Galadriel’s hope for him, even at the cost of abandoning Thorin and company. Now, the high fells of Rhudaur do not exist in the books, but it seems like the ringwraiths are to play a clearer and more present danger in the final assault against Dol Guldur in the last film.

More importantly, this extra bit of time with Beorn talking of faraway places further cements his participation in the Battle of the Five Armoes later. The skin-change concludes with “I remember a time when a great evil ruled these lands. One powerful enough to raise the dead. If that enemy has returned to Middle-earth, I would have you tell me.” Again, I’m not entirely comfortable with Beorn knowing much about the dead, but this line is a certain clue that we’ll be seeing him again.

Fast forward to Lake-town once more! Once Bard has smuggled the dwarves in—itself a significant departure from the book!—we get our first hobbit-eye view of the “world of Men.” Men, of course, will play a larger role in the Battle of the Five Armies and in the Rings trilogy. Up to this point, we’ve been watching fantasy races interact with other fantasy races: dwarves with Elves with shapechangers with wizards with orcs with trolls. Time to see what sort of shenanigans those dirty, short-lived humans are up to!

We also get a better glimpse of Bard’s role as the “protector of the common folk” as a group of fishmongers and fishwives help him subdue some guards seemingly without the bargeman even asking for it. Given Bard’s ancestry and his post-war future, the aid is felicitous. Seeing that he is already respected by the downtrodden shows that he’s not alone as a “troublemaking rebel.” But it’s also a curious addition. A great deal of conflict was added by Jackson to Lake-town’s social and political standing. Consider that Thorin announces himself immediately for who he is in the book—the rightful King Under the Mountain—the moment he approaches the gate. But I suppose, above all, the added time helps us care about the city more before it’s punished by Smaug later.

Though, and we get to see a clever and briefly humorous side to Bard as he pisses off the captain of the guard with a dress and a double entendre.

Arguably the most interesting “extension” is the introduction of Thrain, Thorin’s father himself, in the flesh. Until now, Thrain, who would have been King Under the Mountain after his own father Thrór, was seen in the prologue of An Unexpected Journey and then only mentioned as having been MIA (not in those words) since the battle outside Moria. Now we get to meet him and discover his fate, first in a flashback’s flashback, then when Gandalf ventures into Dol Guldur. Which is a bit of a change…

While there are scads of individual changes between books and films, none of them are so drastic as the shift in Middle-earth’s timeline. Peter Jackson created an urgency in his movies that’s really more of a slow boil in the books. It works in the books because the scope and tone isn’t quite the same, but by comparison it sure makes it seem like there’s plenty of time to get things done on Arda! Have an über-powerful and irredeemably evil artifact to destroy before a Maia spirit reclaims it? Better get to it! But if you’d like to stop and indulge in the food and hospitality of earth gods, innkeepers, Ents, and Elves, well we think that’d be okay. Mount Doom isn’t going anywhere.

Case in point: In the book, even when Gandalf suspects that the ring left to Frodo is the One Ring, he sits on that information and bides his time. Years pass. When he finally becomes certain, he returns to the Shire in April of the year 3018 and encourages Frodo to “go quietly…soon, not instantly,” agreeing that he should do so by autumn (Frodo leaves on September 23rd). Of course, for the films, Peter Jackson didn’t want to add more diegetic time in his films. If he had, they’d be longer still and oh how moviegoers would whine! So there is a greater sense of urgency that works better on the silver screen.

Even the journey from Lake-town to the secret door of the Lonely Mountain takes days in the book, with ponies to help. Smaug had been sitting on that treasure for 171 years. What’s another few days? The significance of Durin’s Day is emphasized more here.

The timeline involving the fortress of Dol Guldur is likewise quite altered. According to the appendices in The Lord of the Rings, Gandalf discovered Thrain in the dungeons of Dol Guldur—and didn’t know who he was, as Thrain himself had forgotten—91 years before Thorin even begins his quest to reclaim Erebor! At that point Gandalf discovered that it was indeed Sauron who occupied the place but it still wasn’t until the events of The Hobbit that he finally convinced the White Council to do something about it. Again, Peter Jackson deemed the discovery and the urgency more relatable for the moviegoing crowd—which I find understandable if awkward. Just when did Thrain give Gandalf the map and key, in this case, and why wait until Bilbo’s house before giving it to him if he knew its significance?

Show, don’t tell, is the common mantra among storytellers of sci-fi/fantasy these days, and Jackson chooses to show where Tolkien could not. Therefore it’s not until The Desolation of Smaug that Gandalf discovers Thrain and reveals Sauron.

The meeting between the wizard and the heir of Erebor is an impactful. Gandalf finds Thrain a tortured, memory-starved creature in Dol Guldur who actually attacks him at first; some wizardly ministrations wakes him up, and we see Gandalf’s regret at having abandoned him for dead long ago. The moment is brief but touching, and it’s clear the two graybeards are also old friends in this version (though “old” is a very relative term in Middle-earth). We also learn that Thrain had worn the “last of the Seven” rings made for dwarves, and that it had been taken from him by force when he was captured by Azog.

We don’t get to see too many Rings of Power in the films, so it’s cool to see another one up close. It’s also a reminder of the burden faced by those who bear them. Someone violent will always wants to take it from you. Little wonder Gandalf doesn’t advertise his.

Aside from the “neat!” factor, there seems little more to this development (at least so far?). Which I actually think is a missed opportunity, given how much talk there is in the Hobbit films of the greed of dwarves. Greed which led to the amassing of riches in Erebor, greed that lured Smaug to the mountain, and of course greed that overtakes Thorin at the end. In the appendices of The Lord of the Rings, it is written that Sauron aided in the forging “of all the Seven.” And though he was unable to control their wearers for “the Dwarves had proved untamable,” he did manage some success:

The only power over them that the Rings wielded was to inflame their hearts with a greed of gold and precious things, so that if they lacked them all other good things seemed profitless, and they were filled with wrath and desire for vengeance on all who deprived them.

As dwarven kings bore the Seven, so the disastrous fate of most of their kingdoms can be pinned on the great Enemy. How perfect would it be to show in the films that he was the author of so many of their woes, where Sauron returns as the great antagonist anyway? Who knows, perhaps there will be something to this later.

Thrain’s final fate is met when Gandalf is kept from leaving Dol Guldur by the nebulous black energy that is Sauron. Interestingly, the moment is both an extended scene and an edited one from the theatrical film. When Gandalf squares off against Sauron, this time Thrain is at his side—CGI’d in!—and tragically resigned to his fate. Against the might of Morgoth’s greatest lieutenant, an Istari wizard like Gandalf will at least hold his own. But a single dwarf mortal? Well, it’s a wonder he was allowed to live this long. (Side note: Worse use of the Wilhelm scream ever, though; very distracting because Thrain is not a throwaway character.)

You can watch most of the extended Desolation scenes on YouTube at this point, but I found them particularly enjoyable woven into the film. Unlike Saruman’s premature demise in the Extended Edition of The Return of the King or the fountain-bathing dwarves in An Unexpected Journey, these feel less “dropped in” and more “placed back.”

Jeff LaSala gave his firstborn son a Quenya middle name and isn’t sorry about it. He has too many Lord of the Rings toys, regularly plays Dungeons & Dragons, and frankly, refuses to grow up. He wrote a couple of SFF novels.